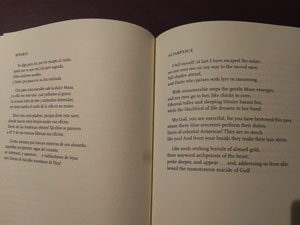

Language—died, brilliant and beautiful

on August 1, 2009 at 2:46 p.m. Lover

of raising his hand, language lived

a full life of questioning. His favorite

was twisting what others said. His

favorite was to write the world in black

and white and then watch people try

and read the words in color. Letters

used to skim my father’s brain before

they let go. Now his words are blind.

Are pleated. Are the dispatcher, the

dispatches, and the receiver. When

my mother was dying, I made everyone

stand around the bed for what would

be the last group photo. Some of us

even smiled. Because dying lasts

forever until it stops. Someone said,

Take a few. Someone said, Say

cheese. Someone said, Thank you.

Language fails us. In the way that

breaking an arm means an arm’s bone

can break but the arm itself can’t break

off unless sawed or cut. My mother

couldn’t speak but her eyes were the

only ones that were wide open.

Notes on the Poem

Over the next few months, our Poem of the Week will feature works from the seven collections of the newly announced 2021 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlist. This week’s poem is from Victoria Chang’s deeply haunting collection, Obit—a series of surreal obituaries extending the definition of what can and can’t be mourned. Chang teaches us how to speak grief, a language in which the unsayable and the mundane coexis—a ghostly, yet deeply material syntax. Of Obit, the 2021 Griffin Poetry Prize judges say: “...Death is not something that happens to someone else—it is yours too, up close and personal, and deeply particular. It is not just a name or person or relation that dies—it is a frontal lobe, language inside the phone, the voicemail, the view and experience, the language they made or didn’t make, their sounds too...Every bit of a lived life gets a spot. In this book ‘grief takes many / forms, as tears or pinwheels...’‘dying lasts forever / until it stops’ and ‘our sadness is plural, but grief is / singular.” In this Rumpus interview, Chang discusses Obit Listen to her read from Obit Here