And so this foreday morning w/out light or choice

i cannot swim

the stone, i can’t hold on to water, so i drown

i swallow left, i turn & fall-

ow into fear & blight, a night so deep it make you turn

& weep the line of spiders of yr future you see spinn-

ing here, their silver

voice of tears, their lid. less jewel eyes .

all thru this buffeting eternity i toss i burn

and when i rise leviathan from the deep . black shining from my skin

of seals, blask tooth, less pebbles mine the shore

haunted by dust & bromes . wrist, watches w/out tone or tides, communion

w/out broken

hands, x-

plosions of frustration, the trans-

substantiation of the sweat

of hate, the absent ruby lips

upon the wrinkle rim

of wine . i wake to tick

to tell you that in these loud waters of my land

there is no root no hope no cloud no dream no sail canoe or dang, le miracle .

good day cannot repay bad night. our teeth snarl snapp-

ing even at halp-

less angels’ evenings’ meetings’ melting steel

in this new farmer garden of the earth’s delights

this staggering stranger of injustices

come rumbelling down the wheel and grave-

yard of the wind, down the scythe narrow streets, clear

air for a moment. clear

innocence whe we are running. so so so so so many. the crowd flow-

to tell you that in these loud waters of my land there is no root no hope no cloud no dream no sail canoe or dang, le miracle . good day cannot repay bad night. our teeth snarl snapp- ing even at halp- less angels’ evenings’ meetings’ melting steel in this new farmer garden of the earth’s delights this staggering stranger of injustices come rumbelling down the wheel and grave- yard of the wind, down the scythe narrow streets, clear air for a moment. clear innocence whe we are running. so so so so so many. the crowd flow-

ing over Brooklyn Bridge. so so so many . i had not thought death

had undone so many melting away into what is now sighing . light

calp from the clear avenue forever

our souls sometimes far out ahead already of our surfaces

and our life looking back

salt. as in Bhuj. in Grenada. Guernica. Amritsar. Tajikistan

the sulphur-stricken cities of the plains of Aetna. Pelée, ab Napoli & Krakatoa

the young window-widow baby-mothers of the prostitutes .

looking back looking back as in Bosnia, the Sudan. Chernobyl

Oaxaca terremoto incomprehende. al’fata el Jenin. the Bhopal

babies sucking toxic milk, our growing heavy furry tongues

accustom to the what-is-the-word-that-is-not-here-in-English beyond ashadenfreude

not at all like fado or duende

Notes on the Poem

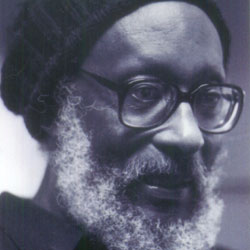

Our Poem of the Week is by Kamau Brathwaite, from the 2006 Griffin Poetry Prize-winning collection Born to Slow Horses.

Of the collection the judges said: “To read Kamau Brathwaite is to enter into an entire world of human histories and natural histories, beautiful landscapes and their destruction, children’s street songs, high lyricism, court documents, personal letters, literary criticism, sacred rites, eroticism and violence, the dead and the undead, confession and reportage. An epic of one man (containing multitudes) in the African diaspora, Brathwaite’s world even has its own orthography and typography, demanding total attention to the poem, forbidding casual glances. Born to Slow Horses is a major book from a major poet. Here political realities turn into musical complexities, voices overlap, history becomes mythology, spirits appear in photographs. And, in it what may well be the first enduring poem on the disaster of 9/11, Manhattan becomes another island in the poet’s personal archipelago, as the sounds of Coleman Hawkins transform into the words and witnesses and survivors. Throughout Born to Slow Horses, as in his earlier books, Brathwaite has invented a new linguistic music for subject matter that is all his own.”

Watch Kamau Brathwaite read from this collection at Koerner Hall here.