Truths are

department stores:

you are going up,

you take the escalator,

you don’t come back

In the tentative

darkness of the

raisins there was

half of the

sun

then the shadow

of the past

Sometimes I get ready for the

voyage of no return,

but dawn raises the curtains,

and my adolescence

is standing at the corner

of nowhere

Under the wonder of

cold skies

Notes on the Poem

What an intoxicating experience, when a poem introduces you to an image, in just a few words captures your attention and fascination ... and then takes you in unexpected directions from what you thought the image might mean. This crisp excerpt from 2020 Griffin Poetry Prize winning collection Time, by Sarah Riggs, translated from poetry originally written in French by Etel Adnan, is endlessly surprising. "Truths are department stores" is a statement that instantly intrigues. A truth is considered an absolute, a single entity. How, then, does that equate to an entity that houses many sections and varieties of items? Or does that single truth house many dimensions? Navigating that single place with many places within it ... well, an escalator is the perfect conveyance, isn't it? Not only is an escalator a piece of everyday magic - that we take for granted while it miraculously transports between building floors, airport terminals, from subway to street and more ... "you are going up, you take the escalator" but it creates illusions that both charm and can cause harm. "you don't come back" With your usual comings and goings, you go and you do come back. What does it mean, then, when a mundane or innocent thought or activity necessitates being ready for a possible "voyage of no return"? Should we always be prepared for the epic and irreversible? This particular escalator - enchantingly but also rather deceptively - is taking you up but never returning you, to the departments through which you have passed, to your adolescence, to your past.

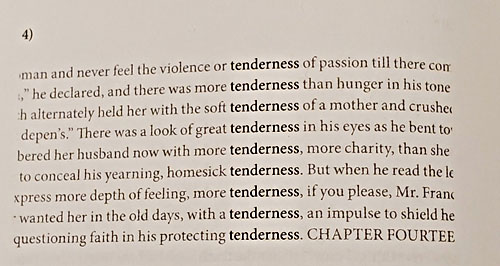

Just looking at those lines drains the word of its usual associations. Stripped bare as part of how Abel has mechanically excavated the term, then determinedly filtered and processed it with acute human consciousness and craft, the word takes on stark and menacing new meanings.

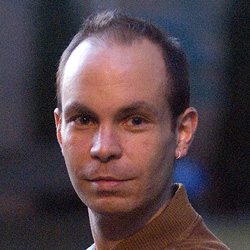

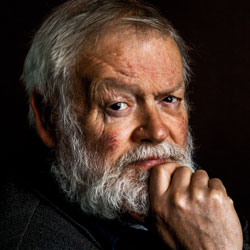

The praise Injun has garnered from Abel's fellow writers captures the value of the poet's steadfast work shaping these unearthed materials.

Just looking at those lines drains the word of its usual associations. Stripped bare as part of how Abel has mechanically excavated the term, then determinedly filtered and processed it with acute human consciousness and craft, the word takes on stark and menacing new meanings.

The praise Injun has garnered from Abel's fellow writers captures the value of the poet's steadfast work shaping these unearthed materials.