TORONTO – Wednesday, June 23, 2021 – Music for the Dead and Resurrected by Valzhyna Mort, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) and The Dyzgraphxst by Canisia Lubrin (McClelland & Stewart) are the International and Canadian winners of the 2021 Griffin Poetry Prize, each receiving C$65,000 in prize money. The other finalists will be awarded $10,000 each.

Grief After Grief After Grief After Grief

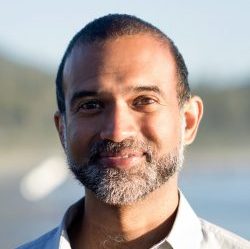

Billy-Ray Belcourt

copyright ©2018

1. my body is a stray bullet. i was made from crossfire. love was her last resort. his mouth, a revolver. I come from four hundred no man’s lands.

2. “smell my armpit again/ i miss it when you do that.”

3. his moaning is an honour song i want to world to.

4. one of the conditions of native life today is survivor’s guilt.

5. it is july 2016 and the creator opens up the sky to attend a #blacklivesmatter protest. there, she bumps into weesageechak and warns him that if policemen don’t stop killing black men she will flood america and it will become a lost country only grieving mothers will know how to find. this, she says, is how the world will end and be rebuilt this time.

6. haunting is a gender. gender is another word for horror story.

7. “i can hear him screaming for me, and i can hear him saying, ‘stop, honey help me.’”

8. i am trying to figure out how to be in the world without wanting it. this, perhaps, is what it means to be native.

2: from Lilting (2014, dir. Hong Khaou).

7: see :h ttp//www.cbc.ca/news/canada/Calgary/rcmp-gleichen-christian-duck-chief-excessive-force-1.3521620

Notes on the Poem

For National Indigenous Peoples Day, our Poem of the Week is “Grief After Grief After Grief After Grief,” by the 2018 Griffin Poetry Prize Canadian winner, Billy-Ray Belcourt from his collection, This Wound is a World (Frontenac House). Of This Wound is a World, the judges said: “Blending the resources of love song and elegy, prayer and manifesto, Billy-Ray Belcourt’s This Wound is a World shows us poetry at its most intimate and politically necessary. Mindful of tangled lineages and the lingering erasures of settler colonialism, Belcourt crafts poems in which “history lays itself bare” – but only as bare as their speaker’s shapeshifting heart. Belcourt pursues original forms with which to chart the constellations of queerness and indigeneity, rebellion and survival, desire and embodiedness these poems so fearlessly explore...This electrifying book reminds us that a poem may live twin lives as incantation and inscription, singing from the untamed margins: “grieve is the name i give to myself / i carve it into the bed frame. / i am make-believe. / this is an archive. / it hurts to be a story.”

A Wake

Liz Howard

copyright ©2016

Your eyes open the night’s slow static at a loss

to explain this place you’ve returned to from above;

cedar along a broken shore, twisting in a wake of fog.

I’ve lived in rooms with others, of no place and no mind

trying to bind a self inside the contagion of words while

your eyes open the night’s slow static. At a loss

to understand all that I cannot say, as if you came

upon the infinite simply by thinking and it was

a shore of broken cedar twisting in a wake of fog.

If I moan from an animal throat it is in hope you

will return to me what I lost learning to speak.

Your eyes open the night’s slow static at a loss

to ever know the true terminus of doubt, the limits of skin.

As long as you hold me I am doubled from without and within:

a wake of fog unbroken, a shore of twisted cedar.

I will press myself into potential, into your breath,

and maybe what was lost will return in sleep once I see

your eyes open into the night’s slow static, at a loss.

Broken on a shore of cedar. We twist in a wake of fog.

Notes on the Poem

This National Indigenous Month, we celebrate voices and poetry that speak to the pluralities of Indigenous identities. Following Jordan Abel, this week’s poem is “A Wake” by the 2016 Griffin Poetry Prize Canadian winner, Liz Howard from Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent (McClelland & Stewart), a collection “filled with energy and magic, suspended between competing inheritances, at home in their hyper-modern hybridity” (Judge’s citation). We also invite you to check out Liz Howard’s latest book, Letters in a Bruised Cosmos (2021) (McClelland & Stewart) “Invoking the knowledge histories of Western and Indigenous astrophysical science, Howard takes us on a breakneck river course of radiant and perilous survival in which we are invited to ‘reforge [ourselves] inside tomorrow’s humidex’. Part autobiography, part philosophical puzzlement, part love song, Letters in a Bruised Cosmos is a book that once read will not soon be forgotten.“ Learn more about Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent in this Jacket2 interview. Listen to Liz Howard read from her collection for the Griffin Poetry Prize

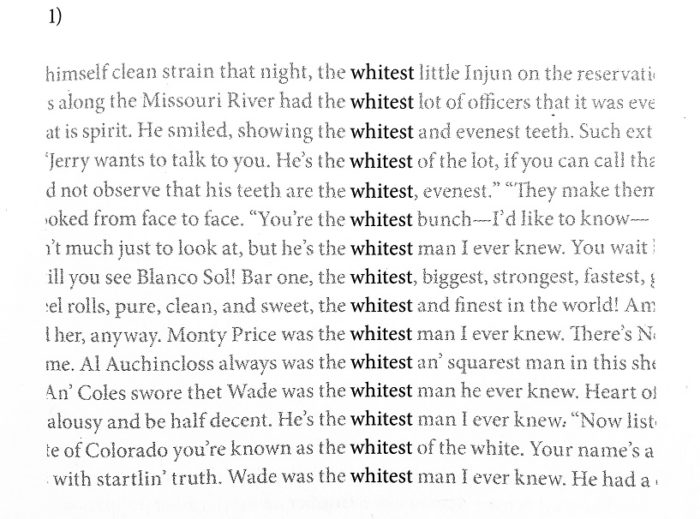

1)

Jordan Abel

copyright ©2016 Jordan Abel

Notes on the Poem

Our Poem of the Week comes from Jordan Abel’s third book of poetry, Injun (Talonbooks) Canadian winner of the 2017 Griffin Poetry Prize. Composed of found texts excerpted from western novels published between 1840 and 1950, Injun displays, through various poetic tools and techniques such as cut-up, pastiche, erasure, and visual poetry, the anti-Indigenous racism permeating Western discourse and literature. Structured around five sections, “Injun,” “Notes,” “Appendix,” “Sources,” and “Process,” Abel subversively re-appropriates academic conventions, diverting their function and troubling their authority. In this visual poem, found in the “Notes” section of the book, we see a stacked repetition of the word “whitest”—a linguistic technique known as concordance line. Abel’s found lines, when collaged together, unsettle and force the reader to confront whiteness and Indigenous erasure head on. As Amaranth Borsuk and Sarah Dowling note, “the transformations Abel enacts upon his source texts mirror the violence settlers enact upon Indigenous societies, but his book’s insistent contemporaneity and vitality—indeed, its beauty and lyricism—demonstrate the myriad ways in which Indigenous peoples persist and endure." We also invite you to also check out Abel’s newly released memoir, NISHGA (McClelland & Stewart) a groundbreaking autobiographical work that collages poetry, art, and archival documents to speak “about intergenerational trauma, Indigenous dispossession, and the afterlife of residential schools.” (Abel, CBC, 2021)

Red Wall

by Tracy K. Smith and Changtai Bi, translated from the Chinese written by Yi Lei

copyright ©2021

Hot. Having burned me but also

Warmed me. I regard it from a distance.

The flowers choking it, bleeding onto it,

Red legacy binding our generations.

From below, we thousands cast upon it a

beatific, benighted, complacent, complicit,

decorous, disconsolate, distracted, expectant,

execrative, filthy, grievous, guileless,

hallowed, hotheaded, hungry, incredulous,

indifferent, inscrutable, insubordinate, joyful,

loath, mild, peace-loving, profane, proud,

rageful, rancorous, rapt, skeptical, terrified,

tranquil, unperturbed, unrepentant,

warring eye.

Notes on the Poem

We begin the week with “Red Wall,” a poem by Yi Lei from her 2021 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection, My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree, translated from the Chinese by Tracy K. Smith and Changtai Bi. “Across the English and the Chinese, readers will hear, perhaps more than anything, the conversation that took shape between Yi Lei’s poetics and my own,” writes Tracy K. Smith in the preface of the collection. The long-lasting friendship and extraordinary collaboration between Smith, Lei, and Bi enabled the translation of this collection in English. This week’s poem, “Red Wall,” captures Yi Lei’s unique personification of the political, the way her erotics are deeply entangled with questions of state, party, and freedom. Not one premised on individualism, but a freedom in which the individual can embrace its collective and ever-shifting composition. In Yi Lei’s poem, the self contains multitudes, just as the enumeration of adjectives used in “Red Wall” expresses the impossibility of reducing experience to a single word. Of My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree, 2021 Griffin Poetry Judges say: “One of shortest poems in My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree creates—in just five lines!—a lasting theological perspective: ‘When life ends, / Memory endures. / When memory ends, / What persists /Attests to the spirit.’ Such larger-than-life—and yet also such delicate—approach distinguishes this collection as it gathers poems of eros and grief, each page bursting with attentiveness to our world. ‘Each blade of grass is a glorious eye,’ Yi Lei writes, echoing, and also revising, Whitman. In very beautiful versions by Tracy K. Smith and Changtai Bi, Yi Lei's voice here becomes invigorating, lasting poetry in English.” Read more about Yi Lei in this LitHub article by Tracy K. Smith and in this New Yorker profile.

From Underworld Lit

Srikanth Reddy

copyright ©2021

In the inky, dismal, and unprofitable research of a recent leave of absence from my life, I happened upon a historical prism of Assurbanipal that I found to be somewhat disquieting. Of an enemy whose remains he had abused in a manner that does not bear repeating here, this most scholarly of Mesopotamian kings professes:

I made him more dead than he was before.

(Prism A Beiträge zum Inschriftenwerk Assurbanipals ed. Borger [Harrassowitz 1996] 241)

Prisms of this sort were often buried in the foundations of government, to be read by gods but not men. Somewhere in the shifting labyrinth of movables stacks I could hear a low dial tone humming without end. In Assurbanipal’s library there is a poem, written on clay, that corrects various commonly held errors regarding the venerable realm of the dead. Contrary to the accounts of Mu Lian, Madame Blavatsky, and Kwasi Benefo, et al., it is not customarily permitted to visit the underworld. No, the underworld visits you.

Notes on the Poem

Our Poem of the Week is excerpted from the 2021 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection Underworld Lit by poet and literary scholar Srikanth Reddy. Resisting categories, Underworld Lit is a genre-bending book of short prose vignettes that weaves troubled dispatches from an untenured academic, class materials from a course on the underworld, a cancer diagnosis, and a makeshift early 20th century French translation of a late imperial Chinese book. In this interview, Reddy offers insightful reflections on the (false) distinctions between poetry and prose. Underworld Lit’s collapse of literary genres isn’t purely formal but a device that blurs the separation between realms and enables the eerie coexistence between the living and the dead. In this opening section of the book, Reddy introduces us to some of the protocols governing the underworld, dispelling “commonly held errors regarding the realm of the dead.” “It is not customarily permitted to visit the underworld.” He writes. “No, the underworld visits you.” Of Underworld Lit, the Judges’ say: “Seldom a poetry book questions its limits in a way as intriguing and inventive as Underworld Lit by Srikanth Reddy. Seriousness and laughter, academic boredom and surreal tour de force, precision and playfulness, the living and the dead move in this book unusually close. A multiverse, a few novels packed in one poetry collection, a delightful and ironic autobiography of a university professor of literature, a book full of disturbingly poetic moments and ironic quizzes, a guided tour to hell. Beautifully balanced and elegantly wild, this prose epic takes us where we truly belong – to the unknown. Reddy – like Dante – knows: If we want to say anything relevant about our world, we have to embark first on a profound tour of the underworld.” Watch Reddy read from Underworld Lit here. Read more about Reddy’s writing process here.

To Antigone, A Dispatch

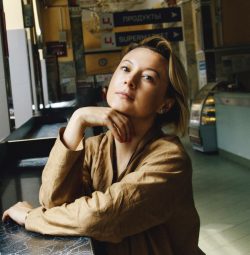

Valzhyna Mort

copyright ©2021

allegro for shooing off the police

adagio for washing the body

scherzo for soft laughter and tears

rondo for covering the body with good earth

Antigone, dead siblings

are set.

As for the living —

pick me for a sister.

I, too, love a proper funeral.

Drag, Dig and Sisters’ Pop-Up Burial.

Landlady,

I make the rounds of graves

keeping up

my family’s

top-notch properties.

On a torture instrument

called an accordion

I stretch my bones

into fingers of a witch.

My guts have been emptied

like bellows

for the best sound.

Once we settle your brother,

I’ll show your forests

of the unburied dead.

We’ll clean the way only two sisters

can clean a house:

no bones scattered like dirty socks,

no ashes at the bottom of kneecaps.

Why bicker with husbands about dishes

when we’ve got

mountains of skulls to shine?

Labor and retribution we’ll share, not girlie secrets.

Brought up by dolls and monuments,

I have the bearings

of a horse and bitch,

I’m cement in tears.

You can spot my graves from afar,

marble like newborn skin.

Here, history comes to an end

like a movie

with rolling credits of headstones,

with nameless credits of mass graves.

Every ditch, every hill is suspect.

Pick me for a sister, Antigone.

In this suspicious land

I have a bright shovel of a face.

Notes on the Poem

We begin this week with Vazhyna Mort’s hauntingly beautiful poem, “To Antigone, A Dispatch,” from her 2021 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection, Music for the Dead and Resurrected. “There are these official historical narratives. But there is also a way of remembering through feeling emotional history — not how it was, but how it felt.” Mort says in a brief NPR interview. In that same interview, she adds that it is difficult to paraphrase a great poem. The same proves true of Mort’s entire collection, a body of work that fearlessly takes on the task of transforming historical data—hundreds of thousands of nameless lives lost at the hands of wars, occupation, and displacement—into grief. “To Antigone, A Dispatch,” places Mort within a lineage of defiant heroines, unafraid to look at History in the face, summoning the power of witches and embracing the darkness needed to speak back to darkness with a new light. Of Music for the Dead and Resurrected, the 2021 Griffin Poetry Prize judges say: “’Here, history comes to an end / like a movie / with rolling credits of headstones,’ writes Valzhyna Mort, though the history doesn't end, but takes deep and memorable residence in the music of these poems. The collection offers many different kinds of poetry: from elegies to protest poems to moments of lyric intimacy. But in all of them there's an unmistakable emotion embodied in craft, one that continues to echo in our minds long after we finish the book. And this is perhaps the reason why Mort's striking pages about Belarus are ultimately poems about all of us: they set our remembering and our grief to inimitable music.” Hear Valzhyna Mort read her poem here. Read this this interview with Valzhyna Mort in Pen America. Listen to her read her poem “A State of Light State of Light," from her collection Music for the Dead and Resurrected here. Read this review by Brian Dillon in 4Columns.

Posthuman

Yusuf Saadi

copyright ©2021

We were busy worshipping

words. Shipping worlds

through string. We held eardrums

to heartbeats to confirm

we were still alive. Someone unchained

the sun from its orbit. We watched it drift

like a curious child beyond the Oort cloud. Dimming

until it was another star in the night’s freckles

and even the day lost its name. We looked

at our hands with unfamiliarity. Trying to understand

the opaqueness of texture. Our moulting bones

discarded. Our new elbows reptilian.

The latest language stripped of meter,

rhyme, beauty. We were warned: there are no straight lines in nature.

Women sang new myths. Men planted

numbers in the soil to see if the fruits

could solve our problems. We invented

new gods and crooned when we remembered

how to brush each other’s hair. Music played

in a distant never. Insects danced

in a different hemisphere of our brain

or of the earth. We often tried to look up,

but we could only see our feet,

alien and hairless.

Notes on the Poem

Our Poem of the Week continues to feature this year’s Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted authors. We’re excited to share “Posthuman” by Yusuf Saadi from the 2021 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection, Pluviophile. Replete with ethereal imagery of night, clouds, and stars, Pluviophile teaches us to “dream-underwater.” It reconfigures our sensory perceptions of the world by creating a new physics of intimacy (“I wish I could touch you—/ not like two electrons repulsing…, but hold you how I hold a hand when I’m afraid—). In “Posthuman,” Saadi imagines a world past the threshold, a place in which humans are no longer humans yet retain a child-like curiosity towards the persistent mysteries of material phenomena. Of Pluviophile, the judges say: “’There are whispers in the letters,’ writes Yusuf Saadi in poems that search everywhere for mystery, for magic, for beauty. And beauty speaks back, renews itself (and us) in these pages. Where other poets find moon, Saadi sees ‘moon's kneecap,’ where others see mere daffodils, Saadi asks: ‘Do daffodils dissolve in your / unpractised inner eye?’ This is the poet who is unafraid of play: ‘Outside of Kantian space and time, do you miss dancing / in dusty basements where sex was once phenomenal?’ This, too, is the poet unafraid of the daily grind, of ‘writing poetry at night / with the rust of our lives’. Pluviophile is a beautiful, refreshing debut.” Learn more about Pluviophile in this interview. Listen to Saadi perform “Root Canal” in this CBC Arts illustrated video.

From The Dyzgraphxst

Canisia Lubrin

copyright ©2021

Here—beginning the unbeginning

owning nothing but that wounding

sense of waking to speak as I would

after the floods, then, after women unlike

Eve giving kind to the so-and-so, trying

to tell them it is time to be unnavigable,

after calling them back to what

the tongue cuts speaking the thing of

them rolled into stone

speaking I after all, after all theories

of abandonment priced and displayed,

the word was a moonlit knife

with those arrivants

lifting their hems to dance, toeless

with the footless child they invent

Notes on the Poem

Our Poem of the Week is excerpted from Canisia Lubrin's 2021 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection, The Dyzgraphxst, a book-length lyrical poem investigating the fractured nature of the colonial subject: “I was not myself. I am not myself. My self resembles something having nothing to do with me,” Lubrin writes. Structured into seven acts, Lubrin’s extraordinary compositional feat turns historical wounds into polyvocal chants that can simultaneously hold violence and offer healing. Of the The Dyzgraphxst, the judges say: “The Dyzgraphxst is Canisia Lubrin’s spectacular feat of architecture called a poem. Built with ‘I’—a single mark on the page, a voice, a blade, ‘a life-force soaring back’—and assembled over seven acts addressing language, grammar, sentence, line, stage, and world, the poet forms, invents, surprises, and sharpens life.??Generous, generating, and an abundance of rigour. A wide and widening ocean of feeling are the blueprints of this book. It is shaped to be ‘the shape of the shape / of the shape of a thing that light curves over time / length to width to depth and all of us its information.’” Listen to Canisia Lubrin read from and discuss The Dyzgraphxst here. Read an interview on her role as Room Contest’s poetry judge here.

Kwantlen

Joseph Dandurand

copyright ©2021

If we talked about the past

we would say how strong our people

were and how they had survived

the constant rains and the great floods

and how they lived in the ground

and how they, like us, took the fish

throughout the year and how it fed

their families. And if we talk about

how they would war against other

river and island tribes who would

come upriver to try to take our people

back with them, we would say

we had great warriors who would wait

for the canoes to come to shore

where we would club them to death.

But today we do not use violence

to survive and we have become quiet

and accepting of our neighbors though

in the beginning we were almost wiped out

as sickness came with the people on ships

who wanted to trade and cheat us of our fish.

That sickness nearly wiped out all river people

but today we are still here, and we survive.

Our children have grown up with loss

and alcohol and drugs and they too fight

for their lives in a world that does not

seem to care about them but we try

to teach them the lessons from a long time

before there was anything written down.

In our ceremonies we repeat those words

and our children will also repeat those words

and so we the river people are still here.

We are all the silent warriors and we say

enough is enough and our young they pick up

the drum and they sing new songs

and they stand and shout to the world

that we are still here and will never leave

this simple island on the great river where

we still take the fish and yes, we still live

where we have been for thousands of years

and we are the ancestors of our future as

a child picks up a drum and begins to sing

a new song given to him from long ago.

Notes on the Poem

Over the next few months, our Poem of the Week will feature works from the seven collections of the newly announced 2021 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlist. This week, we’re excited to share Kwantlen, a poem by Joseph Dandurand from The East Side of It All, a collection that weaves harsh depictions of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside’s street life to stories in which humans, nature, and land are ancestrally entwined. Dandurand writes from a time “before there was anything written down,” celebrating the survival of Indigenous legacies in which storytelling carries forth a generational wisdom indispensable to surviving this late-capitalist age. Of The East Side of It All, the 2021 Griffin poetry prize judges say: “Joseph Dandurand is a poet-storyteller. Portraying Vancouver's Downtown Eastside's prostitutes, heroin addicts, alcoholics and abused, his autobiographical poems could easily drown in the brutality and tragedy they capture – but instead they heal. These are deeply moving spiritual invocations, extricated from poisoned air by a fallen angel. Dandurand is a member of Kwantlen First Nation, located on the Fraser river near Vancouver. His origin and roots are the sources of wisdom and myths, which he masterly embeds in a drama of a dysfunctional modern society. His crystalline clear and remarkably multilayered poems are written in an unforgettable voice of someone who is telling a story in order to survive and to go on. A story of a man who has become a sasquatch, through writing.” Listen to Dandurand discuss his writing trajectory here and here.