I’m bouncing across the Scottish heath in a rented Morris Minor

and listening to an interview with Rat Scabies, drummer

of the first punk band, The Damned, and Mr. Scabies,

who’s probably 50 or so and living comfortably on royalties,

is as recalcitrant as ever, as full of despair and self-loathing,

but the interviewer won’t have it, and he keeps calling him “Rattie,”

saying, “Ah, Rattie, it’s all a bit of a put-on, isn’t it?”

and “Ah, you’re just pulling the old leg now, aren’t you, Rattie?”

to which Mr. Scabies keeps saying things like

“We’re fooked, ya daft prat. Oh, yeah, absolutely – fooked!”

Funny old Rattie – he believed in nothing, which is something.

If it weren’t for summat, there’d be naught, as they say

in that part of the world. I wonder if his dad wasn’t a bit of a bastard,

didn’t drink himself to death, say, as opposed to a dad like mine,

who, though also dead now, was as nice as he could be when he was alive.

A month before, I’d been in Florence and walked by the casa di cura where

my son Will was born 27 years ago, though it’s not a hospital

now but a home for the old nuns of Le Suore Minime del Sacra Cuore

who helped to deliver and bathe and care for him when he was just

a few minutes old, and when I look over the gate, I see three

of these holy sisters sitting in the garden there, and I wave at them,

and they wave back, and I wonder if they were on duty

when Will was born, these women who have had no sex at all,

probably not even very much candy, yet who believe in something

that may be nothing, after all, though I love them for giving me my boy.

They’re dozing and talking, these mystical brides of Christ,

and thinking about their Husband, and it looks to me

as though they’re having their version of the sacra conversazione,

a favorite subject of Renaissance artists in which people who care

for one another are painted chatting together about noble things,

and I’m wondering if, as I walk by later when the shadows are long,

their white faces will be like stars against their black habits,

the three of them a constellation about to rise into the vault

that arches over Tuscany, the fires there now twinkling,

now steadfast in the chambered heart of the sky.

Notes on the Poem

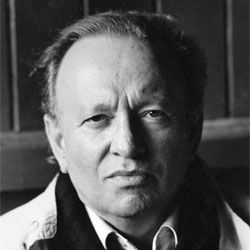

David Kirby's poetry - not to mention the way in which he presents it in readings - is noted for its accessible and even conversational tone. If you heard him read this poem before seeing it on the page, would you be surprised by the seemingly contradictory form of the poem? The consistent, rather formal structure of "The Little Sisters of the Sacred Heart" on the page (or screen here - although screen layouts of poetry are a story unto themselves) seems to contradict Kirby's charming, rambling storytelling. Or is it the other way around? That is, the seemingly unstructured but not unpleasant unfolding of the narrative, or of two seemingly unrelated stories, seems to tweak the formality of how it's all laid out on the page. Then again, the ordered spaciousness and conscientious spacing of the poem's layout makes clearer any number of parallel structures and commonalities between the two ostensibly diametrically opposed stories, and ends up making them startlingly resonant as they're set side by side. Rat Scabies (who "believed in nothing, which is something") was probably in his raucous punk rock heyday at the same time that David Kirby's infant son was being carefully and lovingly attended to by the holy sisters ("who believe in something / that may be nothing"). Years later, possibly those same holy sisters are peacefully engaging in holy and sacred conversation, while Mr. Scabies is ranting with despair that "we're fooked". What else does David Kirby say about the bitter punk rocker and the gentle, steadfast nuns by observing them both in this fashion? What does David Kirby suggest about himself, as the narrator and captivated listener and observer of both Mr. Scabies and the Little Sisters of Sacred Heart?