Griffin Poetry Prize 2011

Canadian Shortlist

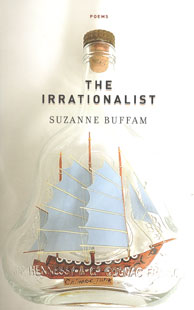

Book: The Irrationalist

Poet: Suzanne Buffam

Publisher: House of Anansi Press

Biography

Suzanne Buffam’s first collection of poetry, Past Imperfect, won the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award for Poetry, was named a Globe and Mail ‘Top 100’ Book of the Year, and was longlisted for the ReLit Award. She won the 1998 CBC Literary Award for Poetry and has twice been shortlisted for a Pushcart Prize. Her poetry has appeared in various literary magazines and journals in the United States and Canada, including Books in Canada, Poetry, Jubilat, A Public Space, The Canary, The Denver Quarterly, Prairie Schooner, and The Colorado Review. Her work has also appeared in the anthologies Language Matters, Breathing Fire: Canada’s New Poets and Breaking the Surface. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and the Master’s program in English at Concordia University, she currently teaches Creative Writing at the University of Chicago.

Judges’ Citation

‘Suzanne Buffam’s The Irrationalist takes nothing for granted. Its rhythms manage to mimic the mind at work, the mind edgy and witty and sharp. The tones are brave and sweeping, ready to re-define the world, alert not only to history and the exigencies of the contemporary, but also to larger questions to do with philosophy, with time and space. Buffam’s talent is to find the startling, telling phrase, arranging and turning her lines and cadences with considerable surprise and flair. Some of the poems are funny; others capture culture and nature, or the connections between them, with intelligence, originality and wisdom. Her poetic systems are bathed in irony, but she is also capable of allowing language to soar. In her three-line poem ‘On Last Lines’, she sums up the power of her own poetic gift: ‘The last line should strike like a lover’s complaint./ You should never see it coming./ And you should never hear the end of it.'”

Summary

With Suzanne Buffam’s second collection, this poet of unusual range, formal rigour, and imaginative force introduces us to the wry meditations of a Chaplinesque literary ‘Irrationalist’ who pursues her own poetic logic beyond the bounds of reason. In the book’s deadpan opening lines our narrator travels nimbly from Genesis to the Age of Exploration to the Cold War, deftly transporting us along: ‘In the beginning was the world. /Then the new world. /Then the new world order.’ Throughout the collection, in resolutely modern, rueful and eccentric lyrics, Buffam investigates the shifting grounds of knowledge while refusing to take any philosophical authority too seriously. Together, these poems compose a swift, durable, protean argument for the necessity of interior maps in a world that may be on the eve of extinction, but whose darkness is continually illuminated by a pyrotechnics of curiosity, candour, and wit.

Note: Summaries are taken from promotional materials supplied by the publisher, unless otherwise noted.

Suzanne Buffam reads Trying

Trying, by Suzanne Buffam

Trying

For a long time we looked at the world and thought not. Then we looked at our lives and thought maybe. Now we are trying. We bought a new set of sheets for the bed. We bought a thermometer and a book.

*

I find the book on the whole reassuring. It gives lots of examples using real-life names like Gail, Audrey, and Dr. Smith, as well as comic touches here and there like Dr. Rhea Sure, who keeps popping up on Gail’s chart. But Appendix K does contain some trying phrases. What, for example, is a Hamster Egg Penetration Assay? What is Nonstimulated Oocyte Retrieval In (Office) Fertilization? What is the Male Factor? What is Within Normal Limits?

*

If procreation were a matter to be decided purely on the basis of rational thought, would the human race still exist? Schopenhauer thought not. Every evening, rain or shine, he would walk his poodle, Atma, for two solid hours through the streets of pre-war Frankfurt, trying to imagine a world as sterile and crystalline as the moon.

*

I try to find it reassuring that Gail is thirty-eight.

*

After swallowing a tiny vial of poison that had weakened over time around his neck, Napoleon escaped his island exile on Elba in the autumn of 1812, having built up a tiny island empire there, replete with tiny army and navy, tiny copper mines, and fields of tiny cabbages and beets. When his ship touched shore he rode bravely out to meet his former soldiers alone and dismounted to address them. The entire Grande Armée turned on the spot and escorted Le Petit Corporal back to Paris, where he renewed his ancient vow to die trying.

*

This morning I tried on my bikini while my husband walked the dog. I turned around and used a compact to study my backside in the mirror above the sink. The mirror, perhaps mercifully, was dusty, and I did not get a good look.

*

The majority of husbands remind me of an orangutan trying to play the violin, said Balzac.

*

My husband, thank heavens, is cooperative. He has even read a few pages of the book. And yet sometimes I worry that it is his fault. That either he is not trying hard enough, or that he is trying too hard, or that no matter how hard he tries or does not try it is his Male Factor that is the problem.

*

While searching for advice on overcoming adversity, I find a book called Tom Cruise: Overcoming Adversity. I learn that the public only sees the glamour – but Phelan Powell shows the significant obstacles Tom Cruise has overcome in order to live his life of pampered opulence. In Cruise’s case dyslexia was one obstacle – it nearly cost him the part of the barman in Cocktail (he thought it was a film about cockatiels and told his agent he ‘didn’t do parrots’) and he bought his own wildebeest to research the part of Lieutenant Maverick Mitchell in Top Gnu. This description is a direct cut-and-paste from an Amazon.com review by a reader named Henry Raddick in London, UK, who gives the book five stars and titles his review: ‘Pig-ignorance no bar to fame and fortune.’ I try to picture what Henry Raddick looks like, and does he live with his mother.

*

The book lives on the back of the toilet and I try to visit it from time to time throughout the day. Sometimes I just look at it. Sometimes I go in there and sit down and open it at random and get lost looking at the pictures. The follicle develops. The egg begins its journey down the tube …

*

The human soul, wrote Aristotle in his treatise on ethics, has an irrational element which is shared with the animals, and a rational element which is distinctly human. In order to live a virtuous life one must try to achieve some sort of balance between them. In his Poetics, however, Aristotle points out that it is exclusively the irrational upon which the wonderful depends for its chief effects.

*

Every morning, before getting up to make breakfast, I record my temperature down to the tenth of a degree on a chart, and draw a line between yesterday’s and today’s. I compare my progress with the sample in the book and try not to worry.

*

People who believe in God will tell you that ‘trying’ to believe will not work. And yet some believers insist that simply wanting to believe is enough. I keep flipping back and forth between trying and wanting to try.

*

In his early twenties it was said that Jean Cocteau could bring himself to orgasm without touching himself, purely by the power of his imagination. Here I am trying to live, he wrote, or rather, I am trying to teach the death within in me to live.

*

When my two oldest friends write to tell me their good news, I try not to let my jealousy show, and sprinkle exclamation marks liberally throughout my replies.

*

Often, I have read, the very act of ‘trying’ can undermine one’s prospects of success. This makes trying difficult. The trick, they say, is to try without actually ‘trying.’ Having finally decided to start trying we must keep on trying while trying not to feel like we are ‘trying’ at all. We must above all try not to worry. Sometimes I worry that I am not trying not to try hard enough.

*

It is one thing to marvel at the miracle of life, but quite another to try to explain it. Almost every freshman biology textbook printed in the last fifty years contains the famous Miller-Urey experiment of 1953, in which Harold Urey and Stanley Miller tried to simulate early atmospheric conditions on Earth, in order to see what they could generate by adding an electrical spark. What they discovered were amino acids, the basic building blocks of life. From there, most books lead straight into a discussion of evolution, prompting the student to conclude that scientists have thus proven life can be created from a few nonliving chemicals. We tell this story to beginning students of biology, admitted Nobel laureate George Wald in his 1954 article, The Origin of Life, as though it represents a triumph of reason over mysticism. In fact, he points out, it is very nearly the opposite.

From The Irrationalist, by Suzanne Buffam

Copyright © 2010 Suzanne Buffam

More about Suzanne Buffam

The following are links to other Web sites with information about poet Suzanne Buffam. (Note: All links to external Web sites open in a new browser window.)

- 12 or 20 questions: with Suzanne Buffam (rob mclennan’s blog)

- Suzanne Buffam profile (Poetry Foundation)

- Suzanne Buffam profile (Canarium Books)

Have you read The Irrationalist by Suzanne Buffam? Add your comments to this page and let us know what you think.

2 Replies to “Suzanne Buffam”