Long enough since the genre was popular

we’ve forgotten what to call it: weird mix of quotes and collectibles, private

thoughts and uncensored meditations in brief, like locks of hair and

child height charts of your considerations

and ponderings. An abandoned art, you practise it with care: each quote

equal to the other, simple entries like coordinates of unmarked

appearances

in the sky – twenty years, over

8,000 days – the weather is “what you make of sunshine,” and only

women “can

make a man successful,” haven’t you heard

“God is the messenger, and we are all brothers and sisters,” organizations

of hate “must be fought with the ultimate crest: humanity,” and you

note a quote with a love reserved

for precision and the unattained, and I

suspend like cracked meteors in the ether

of your common message: go to bed, what is truly important in this world

has already been said.

“When people deserve love the least

is when the need it the most,” we are the axis

of cliche, “like mother like daughter,” sign your name

on this one before I turn out the light

and resume my interrupted prayer.

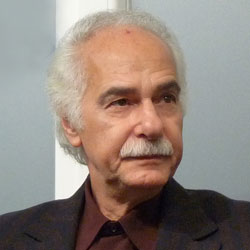

Notes on the Poem

We miss Priscila Uppal's vibrant presence. We are so grateful she left us countless gifts of her urgent, provocative and stirring words, in myriad prose and poetic forms. There seems to be a tussle going on in Priscila Uppal's poem "Common Book Pillow Book", starting right from the title. Let's revisit what it might all be about. The "common book" in the title is probably what the poem's narrator means as a commonplace book. Notebooks used to collect various kinds of information of interest or pertinent to the note taker, commonplace books are not meant to be diaries. They are supposed to be compendiums used as aids for remembering concepts and facts. Of course, no commonplace book capturing someone's interest in a subject or subjects is likely to be utterly dry and devoid of perspectives. A pillow book, by contrast, is intended to encapsulate personal work - observations, musings, sketches, fragments of poetry and more. Even the name, in comparison to the commonplace book, sounds much more intimate. Has Uppal then created some kind of hybrid, in what she describes as a ... "... weird mix of quotes and collectibles, private thoughts and uncensored meditations in brief, like locks of hair and child height charts of your considerations and ponderings." Is that mashup of the factual with the wistful creating tension for the "you and I" of this poem? The dismissive "go to bed, what is truly important in this world has already been said." ... seems to suggest that, don't you think? But as we revisit this poem, perhaps what we originally perceived as dismissive could also be read as practical and, in its way, strangely comforting.