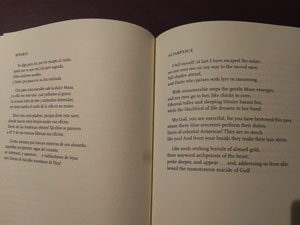

A rare dish is right for those who

have lain bandaged in a tomb for weeks:

quince and quail to demonstrate

that fruit and birds still grow on trees,

eels to show that fish still needle streams.

Rarer still, some blind white crabs,

not bleached but blank, from such

a depth of ocean that the sun would drown

if it approached them. Two-thirds

of the earth is sea; and two-thirds of that sea

-away from currents, coasts and reefs –

is lifeless, colourless, pure weight.

Notes on the Poem

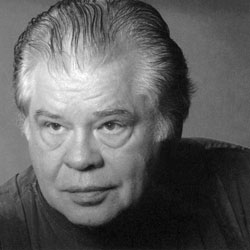

Michael Symmons Roberts is consistently identified as and commended for being a poet who produces works that skilfully juxtapose religious and secular themes. This selection from the poem sequence "Food for Risen Bodies" from his 2005 International Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection Corpus is a striking example of the fine balance he achieves. In a 2014 article in The Irish Times, poetry editor Gerard Smythe profiles Roberts, observing "He is a poet as much immersed in the sensory world as in the transcendent moment and equally at home in scientific knowledge ... as in the revelations of scripture." The first stanza of Roberts' poem refers to resurrection, a concept perhaps unimaginable without some kind of spiritual faith. The poem's first words strike a celebratory note ("a rare dish is right") for those who have literally or figuratively conquered death. From this hopeful opening, the preparations for that celebration turn to the ecological: "fruit and birds still grow on trees" and "fish still needle streams" and then turn even deeper, to parts of our world perhaps as unimaginable as the concept of resurrection if it was not for the efforts of and faith in scientific exploration. The "rare dish" contemplated at the beginning of the poem has a positive connotation, but when we get to "Rarer still, some blind white crabs" an ominous tone seems to take over, as we proceed deeper, as there is the threat of the sun being extinguished, as everything becomes bleached of colour ... and drained of life. Roberts has taken us full circle in six brief stanzas. What might he be suggesting?