In darkness. In rain. Yourself at the very point

where what’s yours bleeds off through the palings

to terra incognito, and the night’s blood-hunt

starts up in the brush: the notion of something smiling

as it slinks in now for the rush and sudden shunt.

A women is laying a table; the cloth

billows as it settles; a wine-glass catches the light.

A basket for bread, spoons and bowls for broth

as you know, just as you know how slight

a hold you have on this: a lit window, the faint

odour of iodine in the rainfall’s push and pull.

Now she looks out, but you’re invisible

as you planned, though maybe it’s a failing

to stand at one remove, to watch, to want

everything stalled and held on an indrawn breath.

The house, the woman, the window, the lamplight falling

short of everything except bare earth –

can you see how it seems, can you tell

why you happen to be just here, where the garden path

runs off to black, still watching

as she turns away, sharply, as if in fright,

while the downpour thickens and her shadow on the wall,

trembling, is given over to the night?

Surely it’s that moment from the myth

in which you look back and everything goes to hell.

Notes on the Poem

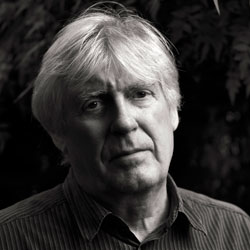

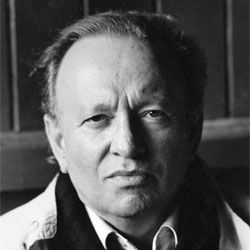

Shouldn't this be a pleasant, warming, welcoming series of images? Why isn't it? How does David Harsent take this innocuous view of a household and garden and give it such a sense of unease? Harsent creates that sense of underlying threat explicitly and from the outset. "In darkness. In rain." That sounds abrupt, stark and unhappy. Swiftly, the poem's metaphors raise the level of alarm with "the night's blood-hunt" and "the rush and sudden shunt". Something is stalking and something is being stalked. But why? The observer standing in the rain and darkness is familiar with the cozy scene that unfolds in the second stanza, a scene with elements "as you know" ... But perhaps "just as you know how slight / a hold you have on this" is the frustrated reason motivating the feeling of menace. Even more pervasive, though, than these and other ominous and specific references ("indrawn breath", "as if in fright") is the overall sense that the poem is not ringing true, but that the note of dissonance is somehow deliberate. Harsent achieves that with different variations of off rhyme, where there is almost a rhyme, but not quite. There are examples of true rhyme in the poem, such as "hunt/shunt", "cloth/broth", "light/slight" and "fright/night". Others are close but oddly off, such as "breath" with either "earth" or "path". The poem even contains intriguing pararhyme combinations where the consonants are the same but the vowel sounds are difference, such as "failing/falling" and "broth/breath". Line after line, all so closely knit, some words rhyming and others having seemingly not fully resolved connections to each other ... has Harsent subtly captured something about the relationship between the person in the garden and the person laying the table in the house?