iii

Once the driver wound a little handle

The destination names began to roll

Fast-forward in their panel, and everything

Came to life. Passengers

Flocked to the kerb like agitated rooks

Around a rookery, all go

But undecided. At which point the inspector

Who ruled the roost in bus station and bus

Separated and directed everybody

By calling not the names but the route numbers,

And so we scattered as instructed, me

For Route 110, Cookstown via Toome and Magherafelt.

Notes on the Poem

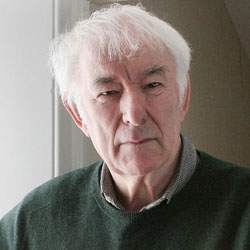

How can simple words on a page manage to create an unmistakable sense of motion and manic activity? Let the deservedly revered Seamus Heaney show us. Heaney creates momentum in this vibrant segment of the poem "Route 110" with straightforward, active verbs and lively images and metaphors. He combines them with increasingly hectic energy that verges on the comic. Heaney starts to transform a bus trip into an animated adventure with the picture of the driver winding a device for displaying destination names as if the entire scene is being wound up like a toy or clock. The word "fast-forward" catapults everything "to life" serving as both adverb and verb, and moving from old-fashioned winding up with a handle to speeding things up with a button or remote control device. Passengers metamorphose into a frantic gaggle of birds, madly off in all directions - that is, "all go // But undecided" until a transit official intervenes and starts directing traffic. The inspector perhaps introduces a modicum of order by "calling not the names but the route numbers", but the harried rooks/passengers still "scatter", even as they comply "as instructed." Seamus Heaney's narrator, however, remembers both his bus route number and the names of the route stops, as if he is calm and directed, moving forward with purpose amidst the wound-up mayhem.