Then she went inland, they say,

taking her mats and all her belongings.

She walked up the bed of the creek,

and she settled there.

Later a trail was cut over top of her.

The traffic disturbed her, she said,

and she moved farther inland.

She sank to her buttocks, they say.

There, they say, she is one with the ground.

When her son takes his place,

she scatters flakes of snow for him.

Those are the feathers.

That is the end.

Notes on the Poem

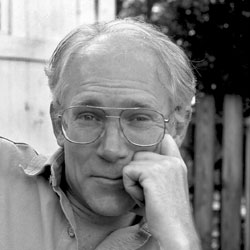

Robert Bringhurst's simply stated language is the foundation of a powerful translation of the work of Haida mythteller Ghandl of the Qayahl Llaanas. This concluding section of "The Way the Weather Chose to Be Born" from Griffin Poetry Prize 2001 shortlisted "Nine Visits to the Mythworld" showcases that power beautifully. The repetition of the phrase "they say" furnishes the poem with mythical heft and resonance. It conveys a sense of legends and tradition passed on - both intimately, one-on-one and collectively - from one storyteller to another. (You can savour more of that rhythmic and pervasive repetition here.) The first stanza is very rooted in the tangible and realistic. You can picture a weary but determined woman hauling her well-bundled possessions over rough terrain, then stopping, unloading and making a place for herself. Then the magical transformations start. The woman becomes part of that terrain, and then that terrain has trails cut in it and traffic materializes, increasing to the point of disruption and intrusion. (Although Ghandl wrote in the late 1800s, don't you picture a highway cloverleaf at this point?) The transformations continue, but the straightforward way in which they are presented makes them organic and believable, as are the snow and/or feathers she provides for her son. As you marvel at the quiet alchemy of Bringhurst's translation, you realize how potently he has connected myth to the realities of present day and how it all still retains human connections.