My pencil, Venus Velvet No. 2,

The vein of graphite ore preoccupied

In microcrystalline eternity.

In graphite’s interlinking lattices,

Symmetrically unfolding through a grid

Of pre-existent crystal hexagons.

Mirror-image planes and parallels.

Axial, infinitesimal bonds.

Self-generated. Self-geometrized.

A sound trapped in the graphite magnitudes.

Atoms, electronics, nuclei, far off.

A break, without apparent consequence.

Near-far, far-near, those microfirmaments.

Far in, the muffled noise of our goodbyes.

The surgeon, seeking only my surrender,

Has summoned me: an evening conference.

We sit together in the Quiet Room.

He cannot ask for what I’m meant to give.

No questions anymore. Just say he’ll live.

A world of light leaks through the double doors,

Fluorescent mazes, frigid corridors,

Polished linoleum, arena sand

Where hope is put to death and life is lost

And elevator doors slide open, closed,

The towers of the teaching hospital.

The field where death his conquering banner shook.

My writing tablet, opened on the table.

I touch it with my hand. The paper thins.

The paper’s interwoven filaments

Are bluish gray and beige. No questions now.

What is the chiefest deed that’s asked of us.

No questions anymore. No questions now.

I turned my back on heaven for good, but saw

A banner shaken out from heaven’s walls

With apparitions from Vesalius:

A woodcut surgeon opening a book

Of workshop woodcuts, skilled, anonymous,

The chisel blade of the engraver felt

Reverberating through the wooden blocks

Among eroded words, ornately carved:

Annihilation, subtly engraved:

All those whom lamentation cannot save

Grown fainter through successive folios.

A seraphy turns a page above: he’ll live;

Then turns a page again: he can’t survive.

I turn the page myself, and write: he’ll live.

Smell of my sweat embedded in my clothes.

The surgeon says: we’ve talked with him; he knows.

A seraph leaning near, Oh say not so.

Not so. Not so. My wonder-wounded hearer,

Facing extinction in a mental mirror.

A brilliant ceiling, someone’s hand on his.

All labor, effort, sacrifice, recede.

And then: I’m sorry. Such a man he is.

Notes on the Poem

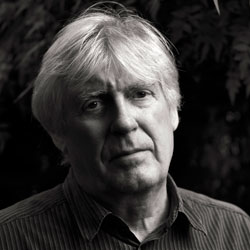

Gjertrud Schnackenberg's arresting collection "Heavenly Questions" is epic in scope, abounding in rich classical references, mythology, science, mathematics. She majestically marshals those themes and sources to circle and zero in on her own pain. This portion of the poem "Venus Velvet No. 2" illustrates well her ability to swoop from the immense to the intimate. As the narrator of this poem awaits devastating news, her pencil and paper are like talismans. Contemplating the organic miracles that make the objects possible distracts her and takes her to other marvellous realms ... where perhaps other miracles are possible. "Atoms, electronics, nuclei, far off." But does the scientific wonder that is graphite, now in her hand, also make her confront the science that can do no more for her own personal situation? "Far in, the muffled noise of our goodbyes." Spiralling in and out of levels of awareness, from the microscopic to the broadly universal and cosmic ("microcrystalline eternity"), Schnackenberg struggles to find where in that vast spectrum she can face and deal with her immense grief and bewilderment. The harsh reality of her situation brings her up abruptly in the midst of this contemplation: "No questions anymore. Just say he'll live." Just as the results of a pencil touching paper can endure for a while, Schnackenberg acknowledges that all ultimately fades ... "Annihilation, subtly engraved: All those whom lamentation cannot save Grown fainter through successive folios."