Some days like pulling teeth, rotten roots.

Staring down the barrel of the gun.

Shooting the town clock.

Forty days in the desert.

Fifty days in the desert, no food and water.

The devil sticking out his tongue.

Electric shock. Thunderbolt.

Heroin. Poison in the veins.

Angels beating their wings on your bared skull.

Who will believe you.

Moon in your hands, transparent, luminous.

Cursed by God.

Cursed by mothers, fathers, brothers, the bloody town hall.

Bereft.

Dogs limping on three paws.

The fourth one sawed off by a car wheel, careening.

The devil making faces.

Long red tongue, goats’ horns, trampling the streets of Ptuj,

announcing spring.

Licking licking. Cunt or wound.

Bad gas leaking from stones, earth fissures.

Nettles. Poison ivy. Bee sting.

Rotgut. Fungus on your toes.

Wild strawberries low to the ground, cheating the lawn mower.

A wall waiting for the wrecker’s ball.

Clear vodka. Ice.

Notes on the Poem

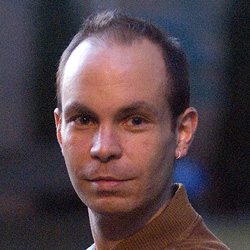

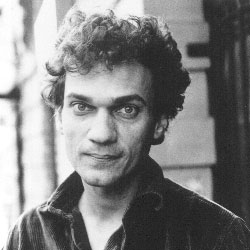

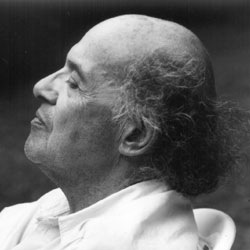

With surprising poetic sleight of hand, Di Brandt builds several layers of sardonic wit and irony using outmoded expressions and clichés in "The poets reflect on their craft", a poem from her 2004 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection Now You Care. Let's explore to what end she applies them. Not only does Brandt unleash a torrent of mean, stale expressions in this poem, she seems to dig deep for ugly ones, such as: "Some days like pulling teeth, rotten roots. Staring down the barrel of the gun." The one about the dogs is maybe a little more original, but it and many other references are still truly nasty. Anton C. Zijderveld, a Dutch sociologist, has pondered the function of cliché in his treatise On Clichés (referenced here):“A cliché is a traditional form of human expression (in words, thoughts, emotions, gestures, acts) which – due to repetitive use in social life – has lost its original, often ingenious heuristic power. Although it thus fails positively to contribute meaning to social interactions and communication, it does function socially, since it manages to stimulate behavior (cognition, emotion, volition, action), while it avoids reflection on meanings.”So then, how are we to respond to this cascade of hideous woe? It looks like writer and reviewer Michael Dennis has found the clue:"There is what Don McKay calls "poetic intention" to the beauty and ugliness, joy and suffering, of everything around you." Di Brandt, You pray for the rare flower to appearThe irony? Take a peek back at the title. Perhaps she's criticizing her peers, but there's probably an equally good chance Brandt is reflecting ruefully and with displeasure on her own work. The additional irony? Buried amidst all the angry, unpleasant clichés are glimmers of beauty and hope: "Moon in your hands, transparent, luminous." "Wild strawberries low to the ground, cheating the lawn mower." "Clear vodka. Ice." Yes, even that last line has appeal, if you want to see it as a boost to the spirit or a toast to new possibilities rather than a gesture of despair. The narrator has reflected on her craft and has decided to stick with it.