The bodies are on the beach

And the bodies keep breaking

And the fight is over

But the bodies aren’t dead

And the mayor keeps saying I will bring back the bodies

I will bring back the bodies that were broken

The broken bodies speak slowly

They walk slowly onto a beach that hangs over a fire

Into a fire that hangs over a city

Into a city of immigrants of refugees of dozens of illegal languages

Into a city where every body is a border between one empire and another

I don’t know the name of the police officer who beats me

I don’t know the name of the superintendent who orders the police officer to beat me

l don’t know the name of the diplomat who exchanged my body for oil

I don’t know the name of the governor who exchanged my body for chemicals

The international observers tell me I’m mythological

They tell me my history has been wiped out by history

They look for the barracks but all they see is the lake and its grandeur the flowering

gardens the flourishing beach

The international observers ask me if I remember the bomb that was dropped on my village

They ask me if I remember the torches the camps the ruins

They ask me if I remember the river the birds the ghosts

They say find hope in hopefulness find life in deathlessness

Locate the proper balance between living and grieving

I walk on the lake and hear voices

I hear voices in the sand and wind

I hear guilt and shame in the waves

I have my body when others are missing

I have my hands when others are severed

I hear the children of Chicago singing We live in the blankest of times

Notes on the Poem

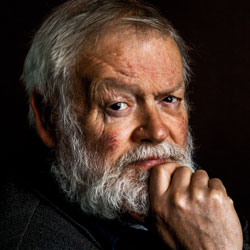

In previous Poem of the Week selections from 2019 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection Lake Michigan, we've observed the hypnotic and incantatory qualities of Daniel Borzutzky's poetry. "Scene 3" is another powerful example that has captured the attention and imagination of high school poetry recitation contest Poetry In Voice / Les voix de la poésie. The poem is potent on the page, but it also exudes tremendous potential to be brought to life as it is read aloud or recited. We've observed this same promise in poems such as "Eight" by Sue Goyette and "A Short Story of Falling" by Alice Oswald. What features of this poem do you think make it a good recitation choice? As it is catalogued in the Poetry In Voice poem database, "Scene 3" is classified as capturing numerous moods that, while cumulatively negative or problematic, offer tremendous dramatic and performative opportunities: angry, anxious, bitter, brutally frank, despairing, furious, helpless, hurt, melancholic, messed up, outraged, tortured. (Note, by the way, that the poem is also classified for older student recitations. Would it be fair to assume that the troubling subject matter and the ferocity with which the poem is asking for it to be conveyed would not best suit younger students?) Another feature of the poem highlighted as a recitation consideration is the use of repetition. Interestingly, the poem repeats words and phrases (such as "I don't know" and "They ask me") but also repeats and slightly varies with each repetition other phrases and sentences, such as those starting with "I" at the end. Would that kind of partial repetition actually make the poem more difficult to memorize? However future student performers approach this poem, we predict their performances of this stunning poem will be ... pretty unforgettable.