When you were first visible to me,

you were upside down, not sound asleep but

before sleep, blue-gray,

tethered to the other world

which followed you out from inside me. Then you

opened your silent mouth, and the first

sound, a crackling of oxygen snapping

threads of mucus, broke the quiet,

and with that gasp you pulled your first

earth

air

in, to your lungs which had been

waiting entirely compressed, the lining

touching itself all over, all inner – now each

lung became a working hollow, blown

partway full, then wholly full, the

birth day of your delicate bellows.

And then – first your face, small tragic

mask, then your slender body, flushed

a just-before-sunrise rose, and your folded,

crowded, apricot arms and legs

spring out,

in slow blossom.

And they washed you – her, you, her –

leaving the spring cheese vernix, and they wrapped her in a

clean, not new, blanket, a child of

New York City,

and the next morning, the milk came in,

it drove the fire yarn of its food through

passageways which had passed nothing

before, now lax, slack, gushing

when she sucked, or mewled. In a month’s time,

she was plump with butterfat, her wrists

invisible down somewhere inside

the richness of her flesh. My life as I had known it

had ended, my life was hers, now,

and I did not yet know her. And that was my new

life, to learn her, as much as I could,

each day, and slowly I have come to know her,

and thus myself, and all of us, and I will

not be done with my learning when I return to where she

came from.

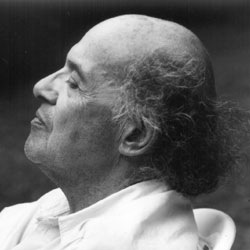

When You Were First Visible

Sharon Olds

copyright ©2019 by Sharon Olds