Lifetime Recognition Award, 2011

On May 31, 2011, revered French poet and essayist Yves Bonnefoy was honoured with The Griffin Trust for Excellence in Poetry’s Lifetime Recognition Award.

Carolyn Forché pays tribute to France’s Yves Bonnefoy at the Griffin Poetry Prize 2011 readings

On behalf of the Griffin Trust for Excellence in Poetry, and my colleagues Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje, Robin Robertson, David Young and Robert Hass, I am honored to present this year’s lifetime Achievement award to one of the greatest living European poets of the present age, M. Yves Bonnefoy of France.

Born in Tours, Indre-et-Loire in 1923, the son of a locomotive assembly worker and a teacher, M. Bonnefoy began writing at an early age. He studied mathematics and philosophy at the University of Poitiers and the Sorbonne, before taking a degree in philosophy at the University of Paris. After the Second World War, he traveled in Europe and the United States, studied art history and was briefly associated with the Surrealists. With his extraordinary book, Du movement et de l’immobilité de Douve, (On the Motion and Immobility of Douve) published in 1953, he embarked upon an original and luminous poetic that he would explore throughout his life, creating a glissement, between poet and other, writer and reader – a poetry of presence and immediacy, intimacy and empathic encounter in the purest diction and most “classically austere forms” of any poet of his generation. In his poetry we find a deep attention to the things of the world; his elemental words are bread, water, stone, tree, earth, sky, blood. His mode is that of wandering – on the frontier of silence, and toward our innermost awareness of presence; he cautions us against excarnation, that call away from the situation at hand, against the refusal of time and death, and asks us to recognize the sacredness of what is.

His poetry embodies a deep quest for the good, the common good. What M. Bonnefoy wrote of the artist Giacometti could also have been said of his own work: “If the art speaks of anything, it speaks of what our society needs, and if that (society) is to exist, and not to degenerate into a hopeless chaos, it is necessary that humans and their right to exist be respected.”

“In fact,” he has said, “it is the speaking-being that has created this universe, even if language excludes him from it. This means that we are deprived through words of an authentic intimacy with what we are, or with what the Other is. We need poetry, not to regain this intimacy, which is impossible, but to remember that we miss it and to prove to ourselves the value of those moments when we are able to encounter other people, or trees, or anything, beyond words, in silence.”

Much more could be said about M. Bonnefoy’s life, and of his twelve poetic works, his translations and writings on other poets and on the artists whom he regarded as poets, but he himself has said “It matters little, in fact, what a man’s life was. It is not necessary to know about it in order to grasp the sense of what he has accomplished. All the more so in that his life grows simpler the moment his work touches greatness. The vocation of creativity has very little need of the accidents of destiny.”

It is as simple as this: “the things that are most full of life on this earth – the tree a face a stone – they must be named. All our hope rests in this.” In another passage he writes, “I would like to bring together – I would like almost to identify poetry and hope.”

Please join me in welcoming to Toronto, as recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award of the Griffin Trust, 2011, M. Yves Bonnefoy of France.

Carolyn Forché

Toronto, May 31, 2011

The Griffin Trust for Excellence in Poetry

At the awards evening on June 1, 2011, Yves Bonnefoy graciously accepted the Lifetime Recognition award with the following speech in English and poem in French.

Mesdames et Messieurs, my first words will be to thank the Griffin Trust and its founders and the members of its jury for the great honour they have bestowed upon me. But I will add that my thanks are also on behalf of poetry as it is written in French, or more precisely, of poetry as it is written today in France. Poetry in the French language is something that you Canadians know quite well, because of many excellent French-speaking poets in your country, and you could forget to pay attention to the poems of the old nation whose language is part of your heritage.

Yes, many thanks. But also on behalf of poetry as such. Because poems may be conceived in French, or English, or Italian, or Polish, but despite this variety of tongues they are everywhere and always the same fundamental intuition, the same specific endeavour which must be recognized as such and helped survive. Therefore I am happy to see that this fact is so well understood by you, in a world more and more overwhelmed by the concerns of science, or technology, or trade.

Why is it so necessary to stress the value of poetry? Because poems, at least the greatest, are not pure artistic creations, beautifully devised, that would answer the desires of only a few persons in a society of leisure. And, on the other hand, because they are not simply the voice of those who, in this world, cruel and unjust as it is, are telling us their predicament, an experience of violence and despair which we could otherwise misunderstand or forget. This latter sort of voice is essential in poetry, of course, and the greatest poems are often those which makes it present in our existence.

But we must also understand that this will to recall the fundamentals of humanity could not flourish, even in these poems, so truthful, without a drive which is deeper in their authors than their astonishment in front of the evils of their time. This motivation? Their memory of the reason why human society has begun, the understanding of the only way for it to continue to exist.

What is poetry indeed ? We are « des êtres parlants », beings capable of speaking, we give our world a form with, mainly, the help of words. But as soon as we speak we are obliged to select particular aspects of the things we are speaking about, it is only with these aspects, these outside aspects of the things, that we give form to our idea of reality, which is our house on this earth. Now, obviously, this sort of simplified universe is more comfortable than the environment that was prevailing before the beginnings of language. Nature has become our earth. Nevertheless, something essential has been lost.

Lost – or, in any case, in great risk of being lost. When we replace the wholeness of a thing, or of a person, by just several of their aspects, we get only an abstract representation of these beings, a figure that is useful, indeed, for the research and discovery of laws, general laws, but is quite unable to keep memory of what the object a word represents is, essentially: an existence, here, now, a presence in front of us at a definite moment of our own lives.

And this is a very dangerous loss. It endangers the other human being as well as the material things. We are replacing persons we know and love by an abstract representation, and nevertheless we believe we know what these persons are, and what is good for them: we risk making of them a cog, just a cog, in the machine which has replaced society. When reduced to concepts and general ideas, language destroys the full presence of the other being in the very field of our own existence.

A very great danger, indeed! But this danger is precisely what poetry is able to detect and wants to refuse and tries to overcome. In the use of words, poetry knows how to identify those that can be more than the vehicle of a concept: but the memory of an existence. The word « tree », for instance, which can help us evoke this particular tree, here, now, with all its branches, all its leaves. Also, poetry listens to the sound of words, a sound which helps the poet to go, through rhythms and music, beyond the conceptual use of our verbs and nouns. Which is recovering the capacity to speak to others as human beings, happy to look at some beautiful tree or to listen to music.

A rediscovery of the Other. Something very important, since it is necessarily the understanding of the right of this other person to be fully himself or herself, his right to think freely – and that is democracy. Poetry is democracy. This simple fact, obvious fact, is the reason why it must be helped to survive.

But now, since you have bestowed upon me this great honour, the Griffin Award, I will try to answer your confidence by making the French sound heard for an instant in this room. Thank you again.

This poem is about a man and a woman, still young, leaving for the last time a house which they had loved. A moment that can be taken for a metaphor of many others.

L’adieu

nous sommes revenus à notre origine.

Ce fut le lieu de l’évidence, mais déchirée.

Les fenêtres mêlaient trop de lumières,

Les escaliers gravissaient trop d’étoiles

Qui sont des arches qui s’effondrent, des gravats,

Le feu semblait brûler dans un autre monde.Et maintenant des oiseaux volent de chambre en chambre,

Les volets sont tombés, le lit est couvert de pierres,

L’âtre plein de débris du ciel qui vont s’éteindre.

Là nous parlions, le soir, presque à voix basse

A cause des rumeurs des voûtes, là pourtant

Nous formions nos projets : mais une barque,

Chargée de pierres rouges, s’éloignait

Irrésistiblement d’une rive, et l’oubli

Posait déjà sa cendre sur les rêves

Que nous recommencions sans fin, peuplant d’images

Le feu qui a brûlé jusqu’au dernier jour.Est-il vrai, mon amie,

Qu’il n’y a qu’un seul mot pour désigner

Dans la langue qu’on nomme la poésie

Le soleil du matin et celui du soir,

Un seul le cri de joie et le cri d’angoisse,

Un seul l’amont désert et les coups de haches,

Un seul le lit défait et le ciel d’orage,

Un seul l’enfant qui naît et le dieu mort ?Oui, je le crois, je veux le croire, mais quelles sont

Ces ombres qui emportent le miroir ?

Et vois, la ronce prend parmi les pierres

Sur la voie d’herbe encore mal frayée

Où se portaient nos pas vers les jeunes arbres.

Il me semble aujourd’hui, ici, que la parole

Est cette auge à demi brisée, dont se répand

A chaque aube de pluie l’eau inutile.L’herbe et dans l’herbe l’eau qui brille, comme un fleuve.

Tout est toujours à remailler du monde.

Le paradis est épars, je le sais,

C’est la tâche terrestre d’en reconnaître

Les fleurs disséminées dans l’herbe pauvre,

Mais l’ange a disparu, une lumière

Qui ne fut plus soudain que soleil couchant.Et comme Adam et Ève nous marcherons

Une dernière fois dans le jardin.

Comme Adam le premier regret, comme Ève le premier

Courage nous voudrons et ne voudrons pas

Franchir la porte basse qui s’entrouvre

Là-bas, à l’autre bout des longes, colorée

Comme auguralement d’un dernier rayon.

L’avenir se prend-il dans l’origine

Comme le ciel consent à un miroir courbe,

Pourrons-nous recueillir de cette lumière

Qui a été le miracle d’ici

La semence dans nos mains sombres, pour d’autres flaques

Au secret d’autres champs « barrées de pierres » ?Certes, le lieu pour vaincre, pour nous vaincre, c’est ici

Dont nous partons, ce soir. Ici sans fin

Comme cette eau qui s’échappe de l’auge.© Yves Bonnefoy

Ce qui fut sans lumière

Mercure de France, 1987

Biography of Yves Bonnefoy

Yves Bonnefoy was born in Tours, France, on 24 June 1923, into a family from Lot and Aveyron. His father worked for the railways, his mother was a schoolteacher. Bonnefoy was educated at Lycée Descartes, in Tours, until the end of “Mathématiques spéciales” (a post-secondary school preparatory year for university mathematics). Later, in Paris, he studied philosophy and held a number of small odd jobs. Between 1955 and 1958, Bonnefoy was a research intern at the CNRS, where he studied Anglo-American critical methodology. An admirer of both Italian and French art, Bonnefoy was among André Chastel’s seminar students at École Pratique des Hautes Études. His career as a writer began in 1946, but really took hold with the 1953 publication of his first book by Mercure de France – who remain his publishers to this day – Du mouvement et de l’immobilité de Douve (On the Motion and Immobility of Douve). Between 1966 and 1972, Yves Bonnefoy co-edited the magazine L’éphémère with Louis-René des Forêts, André du Bouchet, Jacques Dupin, Michel Leiris and Paul Celan. Bonnefoy, the poet, is also an art historian (Rome 1630, Giacometti) and a poetry scholar (Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Mallarmé). Between 1993 and 2004, he hosted an annual conference entitled « La conscience de soi de la poésie », exploring poetic function throughout history. He has translated Yeats, Petrarch, Keats, Leopardi and Shakespeare (Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear, Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, A Winter’s Tale, The Tempest, Anthony and Cleopatra, Othello and As You Like It, among others).

In 1960, Yves Bonnefoy began lecturing as visiting professor at a number of universities in France, Switzerland and the United States, before being elected Chair of Comparative Studies of the Poetic Function at the Collège de France in 1981. He has held the post of Professor Emeritus there since 1993. Yves Bonnefoy is married, has one child and lives in Paris.

Bonnefoy’s many awards include the Prix des Critiques, the Prix Montaigne, the International Balzan Prize, the Del Duca prize and the Franz Kafka Prize in Prague, as well as a number of other prizes from a variety of countries (Italy, Japan, China, the United States and Germany). He has received honorary doctorates from Chicago University, Trinity College Dublin, Edinburgh University, Oxford University, Neuchâtel University, Roma Tre University, Siena University and the American University of Paris. He is also an Honorary Foreign Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Learn more about Yves Bonnefoy:

- Yves Bonnefoy profile (Books and Writers)

- Yves Bonnefoy profile (Poetry International Web site)

- Feature: Judith Bishop on Yves Bonnefoy (Jacket magazine)

- Interview with Yves Bonnefoy (The Paris Review)

- Yves Bonnefoy at 90

Photo credits:

Yves Bonnefoy, by C. Sigel

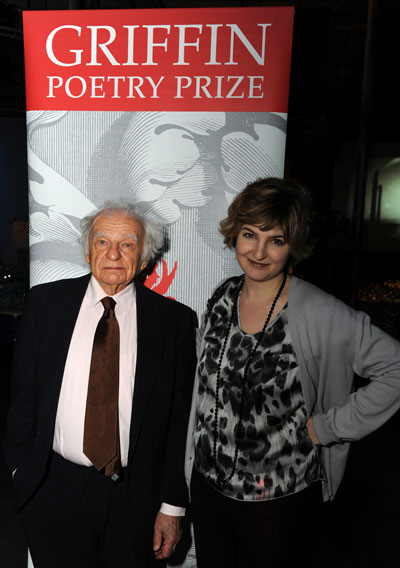

Griffin event, by Tom Sandler Photography

Yves Bonnefoy attends the 2011 Griffin Poetry Prize awards evening with his daughter, Mathilde Bonnefoy.

“His poetry embodies a deep quest for the good, the common good.”

Carolyn Forché’s tribute to Yves Bonnefoy

The Griffin Trust For Excellence In Poetry was saddened to learn of Yves Bonnefoy’s passing on July 1, 2016. The world responded swiftly and with heartfelt words to this tremendous loss to arts and letters:

- Mort d’Yves Bonnefoy, poète, traducteur et critique d’art

(Le Monde) - French poet Yves Bonnefoy dies

(BBC News) - Avec Yves Bonnefoy, une voix majeure de la poésie contemporaine s’éteint

(Le Devoir) - French poet Yves Bonnefoy dead at 93

(France 24) - Contemporary French poet Yves Bonnefoy dies at age of 93

(The Japan Times) - The American Side of France’s Greatest Postwar Poet

(The New Yorker) - Yves Bonnefoy obituary

French poet and essayist who believed in the sacredness of the here and now

(The Guardian)

One Reply to “2011 – Yves Bonnefoy”