Griffin Poetry Prize 2009

International Shortlist

Book: The Lost Leader

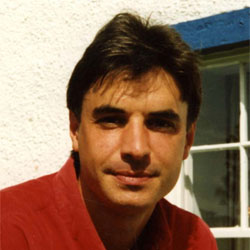

Poet: Mick Imlah

Publisher: Faber and Faber

Biography

Mick Imlah was born in 1956 and brought up near Glasgow and in Kent. He was editor of the Poetry Review from 1983 to 1986, and had worked at the Times Literary Supplement since 1992. He edited The New Penguin Book of Scottish Verse (with Robert Crawford, 2000) and made selections of the poems of Tennyson and Edwin Muir for Faber and Faber. The Lost Leader is Mick Imlah’s first collection of poetry in 20 years. It won the 2008 Forward Prize and was shortlisted for the 2008 T. S. Eliot Prize. In the autumn of 2007, Mick Imlah was given a diagnosis of motor neurone disease (also known as ALS/Lou Gehrig’s disease) and died on January 12, 2009. He is survived by his partner, Maren Meinhardt, and their two daughters.

Judges’ Citation

“Mick Imlah’s masterful The Lost Leader is populated by voices and revenants that point to or joke with or slip in bits of the ballads, songs, and legends of Scotland that his elder Edwin Muir said ‘no poet in Scotland now can take as his inspiration’. Muir’s observation or injunction invites Imlah to wonder who or what can guide him now. He answers with the beautifully idiosyncratic, local, learned, teeming poems in this startling collection – the work of twenty years. Fiercely unelegiac, the book keeps equal company with the dead and the living, in its combination of demotic, modern, and archaic speech, trading in stories of legend, prophesy, insult, sport, alcohol, love, and neglect. Haunted by forgotten figures, lost guides, the divided, leaderless, often feckless characters in Imlah’s poems have to make their own way, now that ‘the fire of belonging was out’. They find temporary forms of shelter, ‘a poor shift made/Between rain and wood’, a room in a boarding house, a telephone box, a literary reputation. The poet himself seems to have declared a homecoming, not to the island Iona but to a child who is given its name. But he still wants to answer ‘the mean/prophetics of a closed book’ for the restless, homeless spirits he has evoked. He ends his own book with the brilliant ‘Afterlives of the Poets’, which draws on the company of Tennyson [celebrated therefore forgotten] and James Thomson [obscure and forgotten], musing on what’s left to us of their lives and pages. He recovers the lost, leaving their books open for us. And, as his closes, he joins their company.”

Summary

Imlah’s approach to Scottish folklore – spanning the Wallace and the Bruce; the Bonnie Prince (pivotal Lost Leader of the title), Robert Burns and Walter Scott; whisky, Clydeside and football – is brilliantly fresh, a modern, sardonic but strongly-felt rendering of Scotland: from AD 500, by way of a guided tour of Iona, to yesterday at a Dumfries bus depot. As the chronicle reaches the twentieth century, the poems turn to friends and family – childhood reminiscences, elegies and celebrations – influenced still by sporting and military fantasy, the charm of history and the power of anachronism.

Note: Summaries are taken from promotional materials supplied by the publisher, unless otherwise noted.

Guillermo Verdecchia reads Drink v. Drugs, by Mick Imlah

Drink v. Drugs, by Mick Imlah

Drink v. Drugs

I was worked up about some other matter

when I saw that phone box off the Talbot Road

being smashed outwards by someone inside it,

after closing on Sunday (Sunday’s the day

they all go mad on crack); which is why

I didn’t as usual walk by on the other side

but advanced with a purpose, and as he swivelled

nonchalant out of the frost, grabbed his lapels,

and setting him roughly against the railings,

‘What is it with you,’ I asked him, ‘drugs?’ –which I knew very well from his vacant expression;

and after he’d cautioned me weakly

against tearing his coat, the stoned boy

answered, matter-of-factly, Yes’ –

and told me which ones, in a Liverpool accent.

It was here I think I said something stupid

about rugby v. football, which he ignored,

rallying rather to call me a prick

and a Good Citizen, and I thought, never mind,

I’m still going to call the police.But that would have meant myself going into

the vandalised box, and releasing my hold,

which maybe he saw, with his pert ‘Go on then’;

then, something better came into his head,

that he would phone, since he hadn’t done nothing;

and moments later he was giving the station

the lowdown on the guy in a light blue shirt

and black jeans who’d assaulted him, seeming

the worse for drink, and accused me of smashing

the phone box from which he was calling now.When in fact I’d begun to warm to the lad –

who’d flattered my stab at authority, kept

a lid on the thing; also I couldn’t be sure,

could I, that he hadn’t been simply clearing away

glass that was broken already, with strong

but not violent blows of the phone.

In any case, when he started to amble off,

I did nothing to stop him; and when the blue

light came quietly round the corner I was standing

alone with nothing to say for myself but my name.From The Lost Leader, by Mick Imlah

© Mick Imlah, 2008

More about Mick Imlah

The following are links to other Web sites with information about poet Mick Imlah. (Note: All links to external Web sites open in a new browser window.)

- Mick Imlah profile and tribute in The Times

- Mick Imlah profile and tribute in The Guardian

- Mick Imlah profile and tribute in The Telegraph

Have you read The Lost Leader by Mick Imlah? Add your comments to this page and let us know what you think.