Griffin Poetry Prize 2005

Canadian Winner

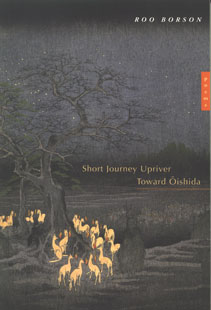

Book: Short Journey Upriver Towards Oishida

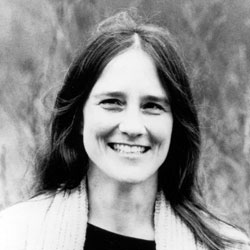

Poet: Roo Borson

Publisher: McClelland and Stewart Ltd.

Biography

Born in California in 1952, Roo Borson has made her home in Canada since graduating with a Master of Fine Arts Degree from the University of British Columbia in 1977. Short Journey Upriver Toward Oishida, also winner of the Governor General’s and Pat Lowther Memorial Awards and shortlisted for the Trillium Book Prize, is her tenth book of poems, which include Water memory (1996) and Night Walk: Selected Poems (1994), a finalist for the Governor General’s Award. In addition to her prize winning essays, Borson’s poetry has won many awards including the CBC Prize for Poetry in 1982 and 1989, and has been a finalist for the National Magazine Awards in 1990 and 1993, the Governor General’s Award in 1984 as well as 1994, and in collaboration with Kim Maltman and Andy Patton as PAIN NOT BREAD, won the Long Poem Prize in the Malahat Review in 1993. Among her publications are: In the Smokey Light of the Fields (1980), Intent, Or, the Weight of the World (1989), Landfall (1977), Rain (1980), A Sad Device (1981), The Transparence of November; Snow (1985) and The Whole Night Coming Home (1984).

Borson has given readings across Canada, in the United States and in Australia, and has been published in a wide array of anthologies including The New Oxford Book of Canadian Verse, the Norton Introduction to Poetry, the Norton Introduction to Literature and The Morningside Papers. She has served as the writer in residence at both Concordia and the University of Western Ontario. Currently living in Toronto with poet and physicist Kim Maltman, along with Andy Patton and Maltman, Borson is a member of the Collaborative performance poetry ensemble PAIN NOT BREAD.

When the Griffin Trust took part in the Dublin Writers Festival in 2005, Roo Borson kept a blog of her observations and impressions – you can read it here.

Judges’ Citation

“To lose ‘North’, in some idioms, is to lose all direction. In her journey, Borson finds North. This is the work of a poet writing at the height of her powers. It is a poetic journal of mortality, of the ‘why be born?’ and ‘do you still love poetry?’, of entering middle age, and of journeying through landscape, seasons, plants, pasts, to find it again. The book is a small perfection in its construction, moving deftly through seasons and forms: poetic prose for a garden of persimmons, haiku rising out of prose sequences for the autumn record, and the book’s fulcrum, the ‘Water Colour’ poems, not haiku but poems that bear haiku’s arrested feeling and succinct observation. As for Basho, Borson’s mentor and poetic ancestor, setting off toward North – lost, loss, losing – is to find the journey itself and one’s own corporeality, out of grief and into the light of words.”

Roo Borson reads from Summer Grass

From Summer Grass, by Roo Borson

From Summer Grass

The willows are thinking again about thickness,

slowness, lizard skin on hot rock,

and day by day this imaging transforms them

into what we see: dragons in leaf, draped scales

alongside the river of harried, spring-stirred silt.

The magpie recites Scriabin in early morning as a mating song,

and home is just a place you started out,

the only place you still know how to think from,

so that that place is mated to this

by necessity as well as choice,

though now you have to start again from here,

and it isn’t home. Venus rising in the early evening

beside the Travelodge, as wayward and causal as

will, or beauty, or as once we willed beauty to be –

though this was in retrospect, and only practice

for some other life. Do you still love poetry?

Below the willows, in the dry winter reeds,

banjo frogs begin a disconcerting raga,

one note each, the rustling blades grow green –

and it tires, the lichen-spotted tin canteen

suspended in the river weeds like a turtle

up for air: such a curious tiredness deflected there.

And what would you give up, in the beautiful

false logic of math, or Greek? In the sum

of the possible, long ago in the summer grass –

Here beside the river I close my eyes: there

the little girls lean continuously across a rusted

sign that says Don’t Feed the Swans

and feed the swans. The swans are reasoning beings;

the young cygnets, hatched from pins

and old mattress stuffing, bright-eyed, learning

what has bread, and what doesn’t. What doesn’t

have to do with this is all the rest:

one more chance to blow out the candles and wish

for things we wished for

that wouldn’t happen unless we closed our eyes.

Not the gingko or the level gaze, or the speaking voice

beneath the pillow, or the waking in the morning

with a name. But cloud – or grief, when grief

is loneliness and you close your eyes. Speech,

when speech is loneliness, and you close your eyes.From Short Journey Upriver Toward Oishida, by Roo Borson

Copyright © 2004 by Roo Borson

More about Roo Borson

The following are links to other Web sites with information about poet Roo Borson. (Note: All links to external Web sites open in a new browser window.)

- Roo Borson profile (University of Toronto – Canadian Poetry)

- Roo Borson profile (Canadian Women Poets)

Have you read Short Journey Upriver Toward Oishida by Roo Borson? Add your comments to this page and let us know what you think.

Photo credit: Sue Schenk

One Reply to “Roo Borson”